Inheritance, severance pay, life insurance payout: there are a few reasons why people get a large sum of money in one fell swoop. Those who want to invest the money in the stock market are faced with the question: should I invest it all at once or rather bit by bit through regular payments into a savings plan? Especially now that the bull market of the last 10 years has come to a close, many people expect more price declines. . Is a lump sum investment too risky? And isn't it better to invest gradually anyway, taking advantage of so-called dollar cost-averaging? Apart from the fact that no one can predict when the next bear market will come, the answer to both questions in most cases is: no. This is illustrated by our example.

An investor wants to invest 100,000 US dollars into a broadly diversified range of stocks - the MSCI World. Because the index is quoted in US dollars, we calculate in this currency. Is the investor worse off or better off with a one-time investment of the entire sum than if they invest 12,500 dollars in month one and then 2,500 dollars in 35 monthly installments? In the second case, the remainder, which has not yet been invested, is left in their current account without interest. For every possible start month since 1989, we calculated which option results in the better outcome after 36 months. It is sufficient to look at just this period because at the end of 36 months all the money is invested, therefore, whichever option is higher in value after three years will remain so.

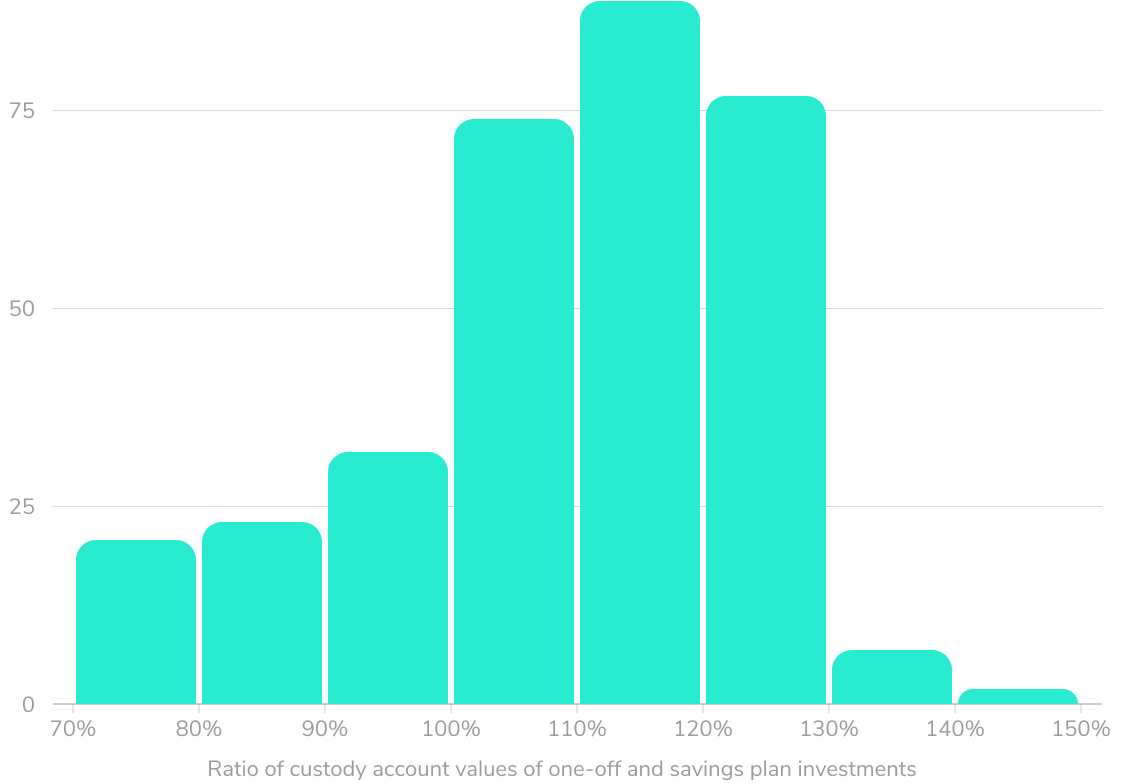

One-off investment beats monthly installments in over 75 percent of cases

The result is quite clear. From the beginning of 1989 to the end of 2018, our investor was able to start a three-year investment at the start of 325 months:

- 249 times, i.e. in three quarters of the cases, they had more money in their portfolio after 36 months with the one-time investment than with the gradual investment.

- In half of the cases, they ended up with at least 12.3 percent more in their account than with the savings plan strategy.

- In a quarter of the cases, it even had an outperformance of more than 20 percent.

Of course, the other side should not be ignored either: In one out of four cases, the one-time investment fell short of the savings plan strategy. More concretely:

- In five percent of the cases, the performance of the one-time investor was at least 22 percent lower after 36 months than with a regular savings plan investment.

- In every tenth case, they had at least 15 percent less money after three years than if they had invested in installments.

One-off investment is usually better than a savings plan

One-off investment of 100,000 US dollars in the MSCI World vs. savings plan with an initial investment of 12,500 US dollars and 35 monthly installments of 2,500 US dollars each*.

Example: In 77 out of 325 cases, the performance of a one-time investment is 20 to 30 percent higher after three years than for a savings plan investment at the same start date.

* Each investment period of 36 months with monthly investment starts from the beginning of 1989 to the end of 2018; with net dividends, excluding trading costs;Source: Bloomberg, own calculations. Note: Neither past performance nor forecasts are a reliable indicator of future performance.

To illustrate the profit and loss potential of the two strategies, we also look at the best and worst case scenarios for absolute performance in three years:

- The worst cases: If the one-time investor invested the whole sum at the beginning of April 2000, when the collapse of the dotcom bubble started, they lost 45 percent of their investment over three years. The savings plan investment led to a maximum loss of 42 percent after three years if the investor put it in at the beginning of March 2006 and thus was fully impacted by the financial crisis.

- The best cases: A one-time investment at the beginning of April 2003, at the end of the dotcom crisis, yielded a profit of 90 percent after three years. The maximum that the investor was able to achieve in three years with the savings investment is half as much at 46 percent and was achieved with a start date at the beginning of 1997, i.e. during the period when the dotcom bubble was building up.

When deciding for or against a one-time investment, however, one should not only look at the extreme cases. After all, these are individual cases, and whether one is on the brink of a crisis or a stock market boom at the time of the investment cannot be predicted anyway.

Statistically speaking, the one-time investment is clearly superior to the savings plan model in our example, as can be seen at a glance from the frequency distribution above. It can be reassuring to invest a large sum in tranches because you don't have to worry about having caught the wrong moment. However, in most cases this will not make you financially better off.

How can the result of our calculation experiment be explained? In the long term, stock market prices tend to rise. An investor who has invested the entire amount from the beginning of a certain period benefits more from the upward trend than an investor who invests the same amount gradually.

Where a savings plan has its strengths

Does the result of our calculation example make the case against savings plans in general? Absolutely not. A savings plan is just not the means of choice for investing a sum of money that is available all at once. Rather, it is suitable for a different purpose: to invest a fixed amount of the money that comes into an account each month, for example as a salary, thereby firmly anchoring regular investing and gradually building up assets. This is where the aforementioned dollar cost averaging effect comes into play: depending on the price development, the investor sometimes buys more, sometimes fewer fund units with their constant savings amount. However, the cost averaging effect should not be misunderstood as an argument in favour of investing large sums of money in small chunks.

Image: Ivan Bandura, unsplash.com

Risk Disclaimer – There are risks associated with investing. The value of your investment may fall or rise. Losses of the capital invested may occur. Past performance, simulations or forecasts are not a reliable indicator of future performance. We do not provide investment, legal and/or tax advice. Should this website contain information on the capital market, financial instruments and/or other topics relevant to investment, this information is intended solely as a general explanation of the investment services provided by companies in our group. Please also read our risk information and terms of use.